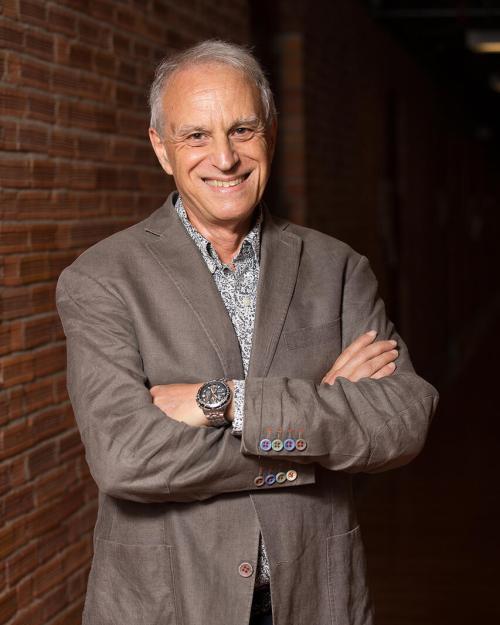

Daniel Gold, professor of Asian studies emeritus, dies at 78

Cornell Chronicle

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences

Department Homepage

The College of Arts & Sciences